Some of the most iconic moments in movie history have involved automobiles. Since the average American spends 200 hours a year commuting to and from his or her job, it’s little wonder cars play such a big role in the stories we tell.

In real life, cars transport us from one place to another, from one “scene” to another, as it were, so it only feels natural to use cars to draw characters and forward the plot in stories. When used well, the car is an extension of character, helping define the person through what amounts as the body armor we choose to wear for much of the time we spend out in public.

Most cars we think of in movies are sexier, faster and obscenely more expensive than the cars we drive, but from a storytelling point of view it’s important to keep in mind that flash isn’t the main goal, but rather a deeper depiction of character.

Remember the cars from these movies?

- From the sixties: James Bond (all of them, beginning in 1962), The Graduate (1967), Bullitt (1968), The Italian Job (1969)

- From the seventies: The French Connection (1971), Harold and Maude (1971), Two-Lane Blacktop (1971), Smokey and the Bandit (1977), Animal House (1978), Grease (1978), Mad Max (1979)

- From the eighties and nineties: The Blues Brothers (1980), Christine (1983), Risky Business (1983), Vacation (1983), Ghostbusters (1984), Sixteen Candles (1984), Back to the Future (1985), Better Off Dead (1985), Cobra (1986), Ferris Beuller’s Day Off (1986), Rain Man (1988), Tucker (1988), Thelma & Louise (1991)

- From the XXI century: Gone in 60 Seconds (2000), The Fast and the Furious (2001), Kill Bill (2003), Batman series (2005 – onward), Little Miss Sunshine (2006), Transformers (2007), Drive (2011)

The above are just some examples of great use of cars in film. But cars often end up in movies because of creative brand placement. Which car ends up in which scenes of movies and television shows is hammered out between producers, screenwriters and the marketers representing car companies. Most film school programs deal with the subject of product placement only tangentially, but it is an enormous financial and promotional consideration for many productions.

It’s a long-held truth that the best product placement is invisible product placement: commodities that make their way into a story in an organic, unobtrusive way. A character has to eat, drink, wear clothes, drive a car, and do all the other things we do, so why not allow him or her to use real-world products, rather than “Greek out” every single prop in the film? The problems arise when characters suddenly talk about or use a brand in a film in a way that screams advertising and not story. Funnily enough, brands actually don’t like this way of forcing their products into stories.

Research has shown that audiences are far more likely to remember—and ultimately consume—products that appear in films and TV shows in which they are emotionally engaged: empirical proof that good storytelling will always trump ham-handed hawking. Because of the money involved, however, we can sometimes find products appearing in films that seem to be an odd fit, or making their way via implausible plot machinations.

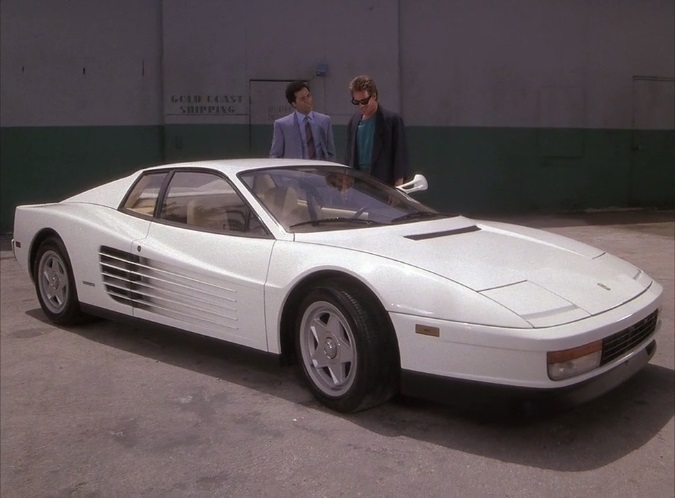

In the ‘80s TV juggernaut Miami Vice, the audience is supposed to accept the fact that two undercover Miami detectives, Crockett and Tubbs, have confiscated a drug dealer’s black Ferrari Daytona Spyder and drive it around as their own (not very undercover, if you ask me). While there was a law on the Florida books at the time allowing for law enforcement to use impounded property for official use, a Ferrari is too indiscreet and worth too much money at auction to just give to a couple cops. The look and fashion of the show about two “MTV cops,” however, reigned supreme, so the producers went with the Ferrari, forgoing plausibility and creating a seminal show in the process. Funnily enough, the car itself was actually a kit car made from a Corvette chassis and outfitted with Ferrari body panels.

After a couple seasons of this, Enzo Ferrari sued the show to get them to stop using this imitation car. The showrunners killed the car in a blaze of glory in the third season premiere, and were rewarded by Ferrari with two brand new genuine Testarossas as replacements. These were white, because Enzo Ferrari thought they would register better in night scenes. This is a rare example of angering a sponsor into providing hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of product for a show. And again, the show was entertaining enough for the audience not to care about the unlikely premise.

Most people agree that NBC’s 30 Rock does an amazing job of incorporating awkward product placement into their show by drawing attention to the very fact that they’re pushing a product out of the blue. In a scene from the show’s first season, Alec Baldwin’s network exec Jack Donaghy holds a meeting in which he tells the staff of the show-within-a-show that they’ll be working product placement into their sketches. Tina Fey’s Liz Lemon replies:

LIZ: “I’m sorry, you’re saying you want us to use the show to sell stuff?”

JACK: “Look, I know how this sounds.”

LIZ: “No, come on, Jack. We’re not doing that. We’re not compromising the integrity of the show to sell—“

PETE: “Wow. This is Diet Snapple?”

LIZ: “I know! It tastes just like regular Snapple, doesn’t it?”

PETE: “You should try Plum-A-Granate. It’s amazing!”

CERIE: “I only date guys who drink Snapple.“

This scene blew minds with its subversion of the heretofore sacrosanct agreement between brands and shows to “slip” product placement unobtrusively into scenes, and instead mined the shoehorning for all its comedic potential. The producers had their cake and ate it too. The show received money from Snapple and earned the respect of its audience. In fact, the technique has become a trademark of the show; the hilariously awkward introduction of a product into the script is a much-anticipated moment in each episode. How brilliant is it that the show is able to make fun of the very products they’re pushing and still get brands begging to be included in the show?

Another great use of product placement comes from funnyordie.com’s Between Two Ferns with Zach Galafianakis. In every episode of this faux-community access cable talkshow, Galifianakis stops his interview subject mid-sentence to pitch his sponsor, Speed Stick. He does this in such an awkward way; it’s a great send-up of commercial sponsorship. Only thing is, Speed Stick does actually sponsor the web series—just look for the banner ads on the page.

One of my favorite stories about automotive product placement is one that almost wasn’t. When Robert Zemeckis and Bob Gale were shopping around their spec script for Back to the Future, the now-famous time machine was…a refrigerator. For years their script was passed on by the studios, until one day an exec (they’re not always wrong) suggested they sex up the time machine a little. And so the flux capacitor-equipped DeLorean was born. And again, the movie directly addresses the product:

MARTY: “Are you telling me that you built a time machine…out of a DeLorean?!”

DOC BROWN: “Yes. The way I see it, if you’re gonna build a time machine into a car, why not do it in style?”

Sage words from the badass who repaired a rift in the space/time continuum while 1.21 gigawatts coursed through his body.

————————

Sonny Calderon is Academic Dean of the Los Angeles campus of the New York Film Academy. He received his MFA from the University of Southern California Graduate Screenwriting Program and has developed several projects for Disney, Fox and CubeVision. Among the award-winning Internet-based branded entertainment pieces Calderon has written and produced is “The Chase,” starring Hilary Duff and Norman Reedus.

Sonny Calderon is Academic Dean of the Los Angeles campus of the New York Film Academy. He received his MFA from the University of Southern California Graduate Screenwriting Program and has developed several projects for Disney, Fox and CubeVision. Among the award-winning Internet-based branded entertainment pieces Calderon has written and produced is “The Chase,” starring Hilary Duff and Norman Reedus.

Bond is in a Studebaker (Leiter’s) at the beginning of the book “Diamonds Are Forever.” There you go.